Dr. Jenny CL Ngai and Prof David SC Hui

Department of Medicine, Princess of Wales Hospital

Case History

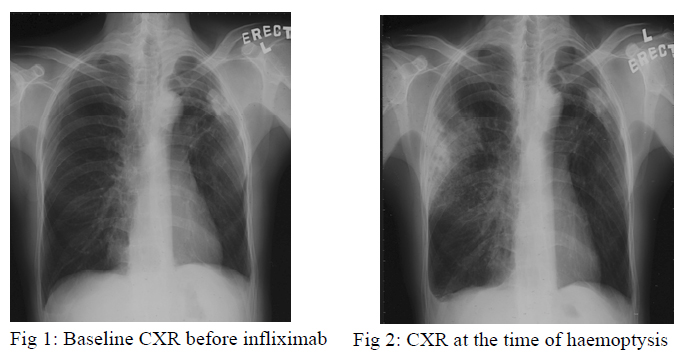

A 47-year old man, with past history of left pneumothorax over 20 years ago, suffered from ankylosing spondylitis for 10 years. Infliximab 800mg every fortnight was started since August, 2005 for treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. His baseline Mantoux test was negative but the chest radiograph, which had been taken before commencement of infliximab, showed a small opacity over the left upper lobe peripheral region (fig 1).

He developed haemoptysis 3 days after receiving the third dose of infliximab at the end of September 2005. There was no systemic symptom. Chest radiograph showed new consolidation at the right upper lobe and static size of the left upper zone opacity (fig 2). Blood tests revealed normal white cell count and raised ESR. Sputum smears for acid fast bacilli (AFB) were negative for three consecutive days and bacteria culture was negative. Infliximab was stopped. Flexible bronchoscopy was performed and bronchoalveolar lavage was negative for AFB smear and bacterial culture. A course of augmentin was given with no clinical or radiological improvement. Fine needle aspiration of left upper lobe consolidation revealed granulomatous inflammation but Zeihl-Neelsen stain and Grocott stain were negative for acid fast bacilli and fungus respectively. Empirical anti-tuberculosis treatment including rifampicin, isoniazid, ethambutol and pyrazinamide were started in early December, 2005.

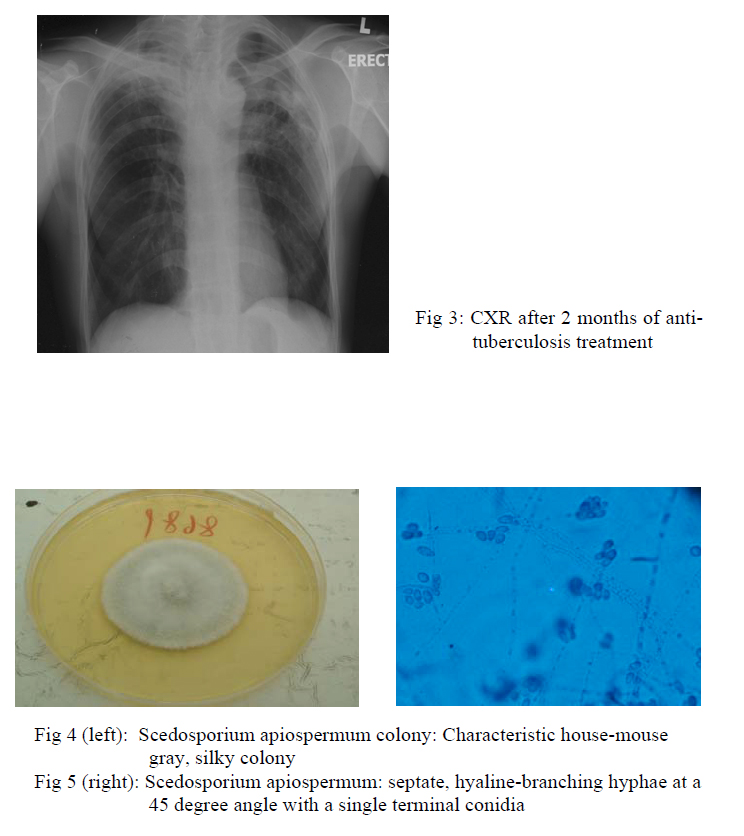

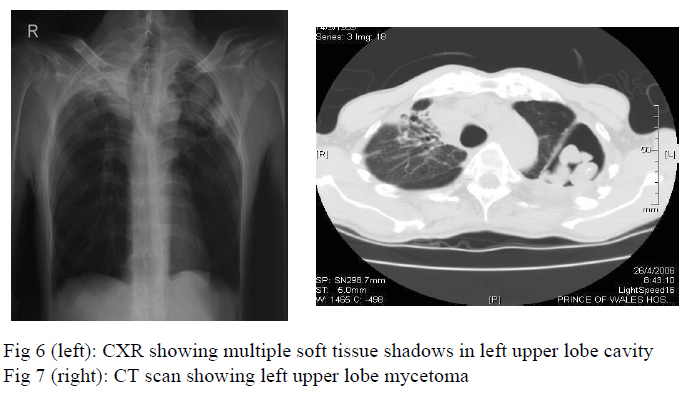

Chest radiograph taken after 2 months of treatment showed resolved right upper lobe consolidation, fibrotic change of right upper lobe and the left upper lobe nodule was static in size (fig 3). However, sputum for fungal culture grew scedosporium apiospermum (fig 4,5). Flexible bronchoscopy was repeated and AFB smear and fungal culture were negative in bronchoalveolar lavage. Computed-tomography (CT) guided fine needle aspiration showed degenerated hyphae only. Patient still experienced haemoptysis intermittently but there was no sign of other organ involvement. Voriconazole was not started in view of localized disease and potential drug interaction with rifampicin.

Two months later, chest radiograph showed a large cavity at the left upper lobe with multiple soft tissue shadows inside the cavity (fig 6) whereas CT thorax showed evidence of mycetoma formation at the left upper lobe (fig 7). In view of persistent haemoptysis and radiological deterioration, voriconazole 200mg daily was started in June, 2006 and the anti-tuberculosis treatment was changed from isoniazid and rifampicin as maintenance therapy to isoniazid, ethambutol, pyrazinamide for 3 more months. He was referred for surgical treatment of symptomatic mycetoma.

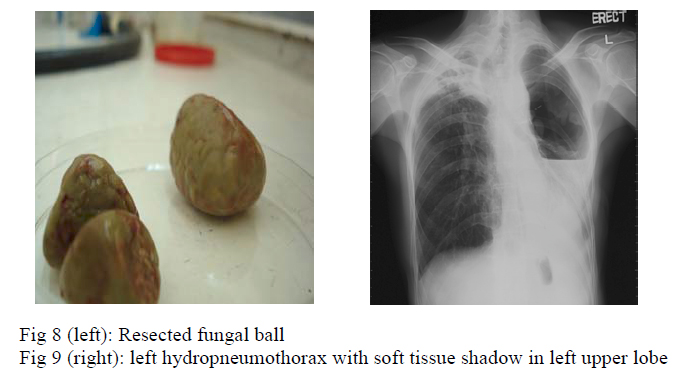

Left upper lobe lobectomy was performed in June, 2006 but it was complicated by aortic perforation, which was repaired successfully. Histology of the resected tissue (fig 8) showed caseous granulomatous inflammation, destroyed bronchial wall with inflammatory cell infiltration, and fungal mycelium was seen. Culture of tissue grew scedosporium apiospermum. Haemoptysis subsided after the surgery and voriconazole was given for 8 weeks.

Eight months later, patient was readmitted because of dyspnoea, purulent sputum and fever for three days. Chest radiograph showed left hydropneumothorax with soft tissue shadow at the left apical region (fig 9). Patient remained in respiratory failure despite chest drain insertion and required invasive mechanical ventilation. He developed septic shock and succumbed 2 days after admission. Pleural fluid microscopy showed large number of white blood cells and gram negative bacilli, with few gram positive cocci. Culture showed moderate growth of Scedosporium apiospermum.

Discussion

Scedosporium infection is increasingly recognized as a cause of infection in severely ill or immunocompromised patients1. Scedosporium apiosperum and Scedosporium prolificans are the two major human pathogens. Scedosporium apiospermum is the asexual form of Pseudallescheria boydii. It can be found in soil, sewage and polluted water. Diagnosis of an invasive mould infection may be made when septate, hyaline-branching hyphae at a 45 degree angle with a single terminal conidia, is identified in a bed of inflammation (fig 5). Aspergillus or fusarium infection also have similar microscopy appearance and a definitive diagnosis can be made by culture. It cause a wide range of pulmonary manisfestations, from simple colonization to mycetoma formation and invasive disease, very similar to that caused by Aspergilllus spp1,2. Coinfection with tuberculosis and scedosporium has been reported3,4. There was no microbiological evidence of tuberculosis infection in this case but the radiological improvement after anti-tuberculosis treatment suggested underlying infliximab related pulmonary tuberculosis coinfection. Treatment option and duration for scedosporium apiospermum have not been established. It is resistant to commonly used antifungal such as amphotericin B and fluconazole whereas voriconazole has the greatest efficacy against the organism5,6. In our case, there was concern that concurrent administration of rifampicin would decrease the serum level of voriconazole. Treatment failure is common in Scedosporium infection and surgical debridement is encouraged as it is associated with better outcome7.

Infliximab is well known to increase the risk of various infections including tuberculosis and fungal infection. This can be explained by the central role of TNF-alpha in development of protective cell-mediated immunity against fungi8. Different fungal infections including histoplasmosis, coccidiodomycosis, aspergillosis , candidiasis and cryptococcosis have been reported to be associated with infliximab. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case report of pulmonary scedosporium as a complication in a patient receiving infliximab.

References

- Koga T, Kitajima T, Tanaka R et al. Chronic pulmonary scedosporiosis simulating aspergillosis. Respirology 2005; 10: 682–684

- Kwon-ChungKJ, BennettJE. Pseudoallescheriasis and Schedosporium infection. Medical Mycology. Lea & Febiger, Philadelphia, 1992, 678–94.

- SeveroLC, LonderoAT, PiconPD et al. Petriellidium boydii fungus ball in a patient with active tuberculosis. Mycopathologia 1982; 77: 15–17

- KathuriaSK, RipponJ. Non-aspergillus aspergilloma. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1982; 78: 870–3.

- Bosma F, Voss A, van Hamersvelt HW et al. Two cases of subcutaneous Scedosporium apiospermum infection treated with voriconazole. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2003; 9: 750–3

- Johnson, LB, Kauffman, CA. Voriconazole: a new triazole antifungal agent. Clin Infect Dis 2003; 36:630.

- Husain S, Munoz, P, Forrest, G, et al. Infections due to Scedosporium apiospermum and Scedosporium prolificans in transplant recipients: clinical characteristics and impact of antifungal agent therapy on outcome. Clin Infect Dis 2005; 40:89.

- Hernadez, Yadira, Herring et al. Pulmonary defenses against fungi. Seminars in Respiratory & Critical Care Medicine. Pulmonary Host Defenses. 2004; 25(1): 63-71