Dr. Wong Tsz Lun, Dr. Chu Wing Yan, Dr. Kwan Hoi Yee, Dr. Yu Chin Wing, Dr. Wong Chun Man, Dr. Lam Wai Kei, Dr. Choo Kah Lin. Department of Medicine, North District Hospital. 21st January 2010

A 61-year-old man was admitted to North District Hospital on 22nd July 2009, presenting with dyspnoea and increased sputum production.

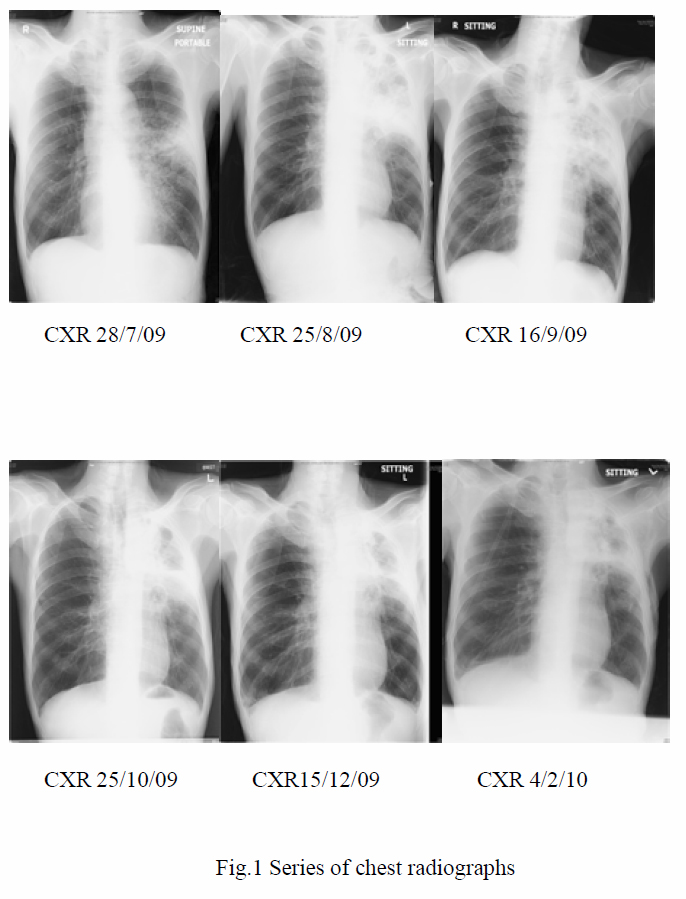

There was no recent travel or contact history. There was also no contact with animals or pets previously. He was afebrile upon admission. Chest examination revealed prolonged expiratory phase. White cell count (WCC) was 12.7x 109/L; Hb 13.4 g/dL; arterial blood gas (ABG): pH7.44; pCO2 4.45 kPa; pO2 17.86 kPa. Chest X-ray was clear. The patient was initially managed as acute exacerbation of chronic pulmonary obstructive disease (COPD) with amoxicillin/clavulanate and systemic steroids. With the subsequent development of fever, Cefoperazon/sulbactam was brought in. Sputum culture later yielded Pseudomonas aeruginosa. However, fever persisted and left middle zone consolidation increased. Antibiotics were then switched to piperacillin/tazobactam and gentamicin on 29th July 2009. Fever did not subside after the two antibiotics were given for another two weeks. Antibiotics that were subsequently employed included imipenem, clarithromycin and amikacin. Sepsis workup was repeated. Patient remained febrile with the pneumonia unresolved. Another sputum culture yielded Stenotrophomonas maltophilia in August 2009 and ticarcillin/clavulanate and co-trimoxazole were subsequently introduced according to the sensitivity profile.

Owing to the unresolved pneumonia, bronchoscopy was performed in August 2009 with no abnormality being detected. Bronchoalveolar lavage was sent for culture, acid-fast bacilli smear and culture, Mycobacterium tuberculosis direct test, Legionella, Pneumocystis jirovecii, fungal and viral cultures as well as cytological examination. Amongst those, only fungal culture was positive, yielding candida albicans. Transbronchial biopsy at the superior lingular segment revealed inflammation and reactive change only. A course of fluconazole was thus given in late August 2009. Other blood tests, including autoimmune markers (MPO, PR3), galactomanann, Aspergillus IgG antibody, methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus screening, anti-HIV antibodies, were all negative.

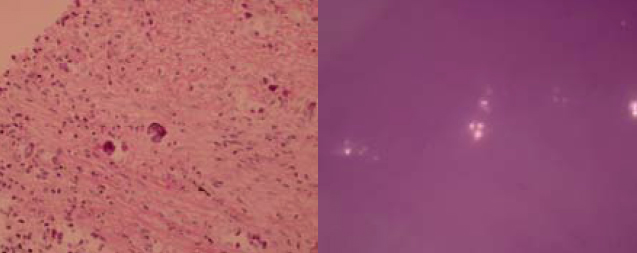

As the condition did not improve and pulmonary tuberculosis was a differential diagnosis with the CXR appearance, empirical anti-tuberculous treatment was started (isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, pyrazinamide) on 4th September 2009. CT-guided biopsy of the lung lesion was subsequently performed. While culture of the biopsy was negative, histology report revealed inflammation, fibrosis, and foreign body giant cell reaction against crystal–like foreign body, nature of which was unknown. It was negative for malignancy and fungal stains (PAS/PASD and Grocott). X-ray microanalysis and the appearance of the crystals under electron microscopy were suggestive of presence of calcium oxalate crystals. (Fig. 2a and 2b) More in-depth history was elicited. Although the patient was a tour guide before the admission, he had worked in a construction site with respirator on for 10 days 8 years ago. He denied history of intravenous drug addiction or inhalational drug abuse. There was no choking on eating. Ophthalmologist was consulted to look for any crystallinopathy or embolism in the fundi, which were absent. Oxalate level in 24-hour urine was 0.32 mmol/day (normal range 0.08-0.49 mmol/day), making possibility of hyperoxaluria less likely.

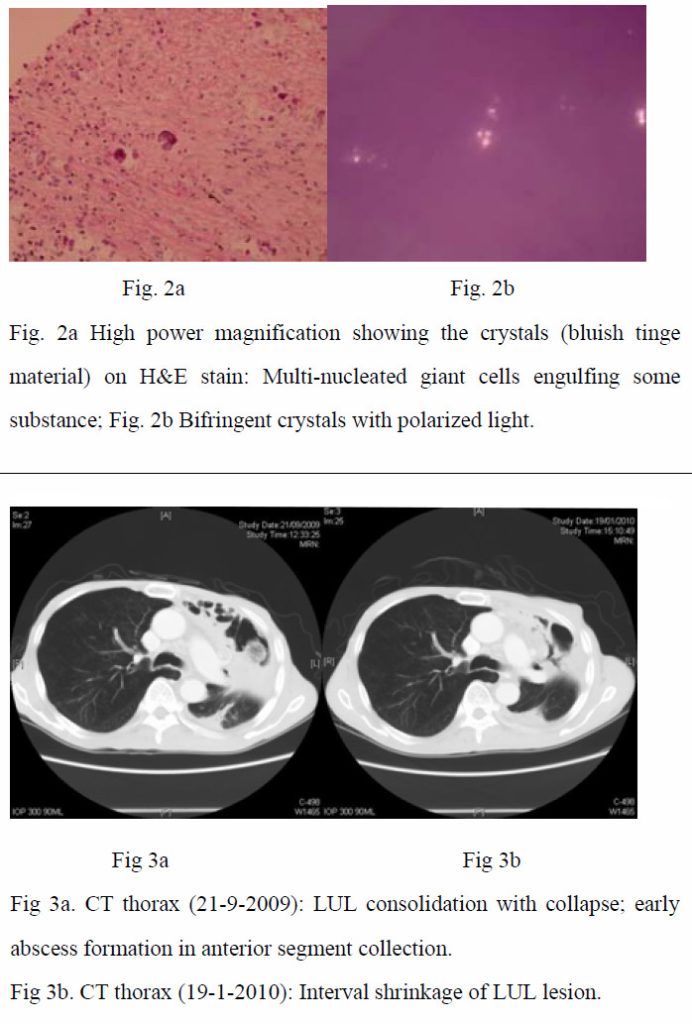

In the presence of inflammatory reactions against calcium oxalate crystals on lung biopsy and the settings of unresolved pneumonia despite multiple antibiotics, the clinical diagnosis of chronic necrotizing pulmonary aspergillosis with pulmonary oxalosis was reached. Voriconazole was started on 1st October 2009. Low grade fever persisted during the first 10 days of treatment. Voriconazole was then replaced by amphotericin B, when the fever eventually subsided. C-reactive protein checked on the ninth day of voriconazole treatment later revealed marked reduction from 146.0 mg/L on 30th September 2009 to 67.7 mg/L on 9th October 2009, which was suggestive of an improvement. Voriconazole was thus resumed. The patient remained afebrile and C-reactive protein went on a downward trend. The patient was subsequently discharged with oral voriconazole. Aspergillus antibody was rechecked, which was positive after discharge. During subsequent outpatient visits, the patient remained afebrile, with improved exercise tolerance and decreased respiratory symptoms. Voriconazole was then changed to itraconazole on 1st February 2010 after cost-effectiveness evaluations. Improvement was continually noted in CRP trend, on CXRs and CT thorax with time (Fig 1, Fig 3a and 3b).

Discussions

In our case, we were given the clue of having crystals in the lungs. According to literature, there are only a few types of crystals in lungs. Charcot-Leyden crystals are eosinophilic structures typically rhomboidal or needle-shaped crystalline by-products of eosinophil granules1 and can be found in hyper-eosinophilia states like asthma and fungal infections.1 Calcium salts like calcium oxalate can be found in fungal infections such as aspergillosis and zygomycosis.5,6,7 Intravascular crystal-like embolus is the third type of crystals present in lungs.3 These can arise from vascular manipulations like vascular surgery.3 In patients with crystal-storing histiocytoma, paraprotein accumulation within the cells accounts for the presence of crystals 4

Calcium salts have been found in fungal infections. While they are usually found in aspergillosis, they have also been mentioned in some case reports of zygomycosis.5,6,7 Amongst the calcium salts, calcium oxalate has been the most commonly identified component.5,6,7 In humans, a direct association has been found between oxalate crystal production and Aspergillus niger or less often Aspergillus fumigatus infection.11 It has been reported that calcium oxalate is a fermentation product of Aspergillus species via the tricarboxylic acid cycle.2,11 Such crystals, as suggested by Yoshihisa et. al., could cause damage to the lung tissue.2 Such damage may lead to fatal pulmonary haemorrhage.11 In addition to the lung tissue, it has been reported that calcium oxalate is also present in sputum. Together with serological assays, this might give the hint for early diagnosis of aspergillus pneumonia. 2

Aspergillus is a soil-residing fungus commonly found in decayed matters like organic debris, dust, compost, food, spices and rotted plants.9 Amongst the approximately 200 species, only a few cause diseases in human beings.9 Depending on the nature of interaction between the host and the aspergillus species, a wide spectrum of conditions can be resulted. In normal hosts, inhalation of aspergillus spores can result in no sequel. Aspergilloma can be found in patients with cavitary lung diseases. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis arises from hypersensitivity reactions. In immunocompromised hosts, Aspergillus can give rise to invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA). In mildly immunocompromised hosts or those with chronic lung disease, chronic necrotizing pulmonary aspergillosis (CNPA) can result. 9

CNPA (commonly due to Aspergillus fumigatus) usually takes a more indolent course, progressing over months to years. There is local invasion, but not vascular invasion and systemic dissemination.9 Although pre-existing cavity is not necessary, most patients have underlying lung diseases like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, inactive tuberculosis, ankylosing spondylitis, recurrent pneumothorax, previous lung resection, radiotherapy, pneumoconiosis, cystic fibrosis and lung infarction.9,10 Sometimes, patients with mildly suppressed immune status like those with diabetes mellitus, poor nutritional status, excess alcohol consumption, chronic liver disease and those on corticosteroid therapy are also more prone to the condition.9,10,12

There are three clinical presentations of CNPA. Chronic productive cough is the most common feature. The second common symptom is haemoptysis, followed by constitutional symptoms like weight loss, malaise, and fatigue.10 CXR typically shows infiltrative process in upper lobes or superior segments of the lower lobes.9 A fungal ball may be seen, with adjacent pleural thickening which can vary from several millimeters to 2 centimeters.9,10 Nearly all patients with CNPA have Aspergillus fumigates precipitins in blood. Yet, the titre of antibodies varies over time and may be negative at some time in the disease course.10 Meanwhile, diagnosis is confirmed by a histological proof of tissue invasion by Aspergillus species and its growth on a culture. However, this is not always possible; so, the following criteria can be used to make a clinical diagnosis of CNPA:9

– Clinical and radiological features consistent with the diagnosis

– Isolation of Aspergillus species by culture from sputum or from bronchoscopic or percutaneous samples

– Exclusion of other conditions with similar presentations, such as active tuberculosis, atypical mycobacterial infection, chronic cavitary histoplasmosis, or coccidiomycosis.

Diagnosis of the condition should be followed by systemic antifungal treatment.10 According to the treatment guidelines of Aspergillosis issued by the Infectious Diseases Society of America in 2008, treatment of CNPA is similar to that of invasive pulmonary Aspergillosis. The greatest body of evidence regarding effective treatment supports the use of oral itraconazole.14 Dupont B. studied the outcome of using itraconazole alone or in combination with or after treatment of amphotericin B and flucytosine in patients with different types of aspergillosis. It was reported that 7 out of the 14 patients with CNPA were cured; significant improvement was noted in six.15 Voriconazole, a newer triazole, is also likely to be effective.14 Juliette Camuset et al. carried out a retrospective multicenter study over a 3-year period from 2001 to 2004 and found that voriconazole provided effective treatment of CNPA with an acceptable level of toxicity.13 However, either lifelong therapy or prolonged therapy is required to halt progression and lead to improvement.10 Alternative antifungal agents (other than triazoles) like liposomal amphotericin B, echinocandins. Intracavitary instillation of amphotericin B has been employed in some cases.14 Since treatment is given in long-term, oral form is preferred over the parenteral route.14 Surgical resection of the diseased part has been shown to be related to significant post-operative complications.9

In conclusion, in patients with chronic lung diseases or mildly immunocompromised states, the presence of calcium oxalate crystals in histological specimen or sputum plus unresolved pneumonia should prompt one to consider chronic necrotizing pulmonary aspergillosis as a possible diagnosis.2

References

- Laucirica R, Ostrowski ML. Cytology of nonneophlastic occupational and environmental disease of the lung and pleura. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2007; 131:1700-1708

- Nakagawa Y, Shimazu K, Ebihara M, et al. Aspergillus niger pneumonia with fatal pulmonary oxalosis. J Infect Chemother 1999; 5:97–100

- Sabatine MS, Oelberg DA, Mark EJ, et al. Pulmonary cholesterol crystal embolization. Chest 1997; 112:1687-1692

- Ionescu DN, Pierson DM, Qing G, et al. Pulmonary crystal-storing histiocytoma. Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine 2005; 129:1159-1163

- Rassaei N, Shilo K, Lewin-Smith MR, et al. Deposition of calcium salts in pulmonary zygomycosis. Human Pathology 2009; 40:1353-1357

- E Mantadaki and G Samonis. Clinical presentation of zygomycosis. Clinical Microbiology and Infection Oct 2009; 15 (suppl. 5): 15-20

- Ghio AJ, Peterseim DS, Roggli VL, et al. Pulmonary oxalate deposition associatged with Aspergillus niger infection. An oxidant hypothesis of toxicity. American Review of Respiratory Disease 1992; 145:1499-1502

- Farley ML, Mabry L, Munoz LA, et al. Crystals occurring in pulmonary cytology specimens. Association with aspergillus infection. Ata Cytologica 1985; 29:737-744

- Soubani AO, Chandrasekar PH. The clinical spectrum of pulmonary aspergillosis. Chest 2002; 121:1988-1999

- Denning DW. Chronic forms of pulmonary aspergillosis. Clin Microbiol Infect 2001; 7(suppl):25-31

- Muntz FH. Oxalate-producing pulmonary aspergillosis in an alpaca. Vet Pathol 1999; 36:631-632

- Binder RE, Faling LJ, Pugatch RD, et al. Chronic necrotizing pulmonary aspergillosis: a discrete clinical entity. Medicine 1982; 61:109–124

- Camuset J, Nunes H, Dombret MC, et al. Treatment of chronic pulmonary aspergeillosis by vorioconazole in non-immunocompromised patients. Chest 2007; 131:1435-1441

- Walsh TJ, Anaissie EJ, Denning DW, et al. Treatment of aspergillosis: clinical practice; Guidelines of the Infectious diseases society of America. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2008; 46:327–360

- Dupont B. Itraconazole therapy in aspergillosis: study in 49 patients. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 1990; 23:607-614